ISSN: 2158-7051

====================

INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF

RUSSIAN STUDIES

====================

ISSUE NO. 9 ( 2020/1 )

|

ISSN: 2158-7051 ==================== INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN STUDIES ==================== ISSUE NO. 9 ( 2020/1 ) |

CHALLENGING SOVIET UNION’S INFLUENCE AND SOVIET BLOC UNITY: UNITED STATES ECONOMIC AID TO YUGOSLAVIA IN EARLY COLD WAR

ZENG QINGMING*

Summary

After

the end of the Second World War, Yugoslavia, as one of the victorious

countries, received various assistances for its post-war reconstruction from

United States, Britain, France and Soviet Union. The Soviets expulsion of

Yugoslavs out of Cominform in 1948 signalized the unfolding of the first

Soviet-Yugoslav conflict, which led to the subsequent economic blockade of

Yugoslavia from Soviet bloc countries. Faced with potential Soviets military

invasion and political subversion, as well as worsening domestic economic

situation resulted from collectivization and drought, Yugoslavia changed its

strategic orientation to the West and turned to United States for help.

American thought the tension between Yugoslavia and Soviet bloc would be used

to further widen the split within the Soviet bloc, so they actively developed

several programs to “keep Tito afloat”. This paper examines the evolution of

the American efforts to aid Yugoslavia in the early Cold War period.

Key Words: Yugoslavia, United States, Economic Aid, Cold War.

Introduction

United States

aid to Yugoslavia in the post-Second World War period started through the

United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRRA) program.

Considered the harsh economic situation in Yugoslavia following the devastating

effect of the Second World War, UNRRA decided to provide grains, powered eggs,

food, clothing, medical supplies to stop mass starvation and to rehabilitate

agriculture in Yugoslavia. Documents from the Yugoslav side suggests that for

July 1945, the UNRRA donated 55, 923 tons of diverse items ranging from

industrial resources like raw materials, to basic necessities like clothings

and food (Yugoslav Archive 1956) to Yugoslavia. From January 1945 until June

1947, UNRRA distributed supplied totaling $415.6 million, of which 72% came

from the United States (Lampe and Russell eds. 1990, 21). Although in the later

period United States was suspicious about how Yugoslavia distributed the

assistance and finally suspended the program in 1947, Americans later clearly

admitted that “UNRRA achievement in Yugoslavia was tremendous” (Geuvjehizian

1963, 21). From October, 1945 to the end of 1946, from 3,000,000 to 5,000,000

people in Montenegro, Slovenia, Herzegovina, Dalmatia, and Croatia were fed

“exclusively” by UNRRA aid; and another 3,000,000 received part of their food

from the same source (Tomasevich 1949, 404-405). With tremendous assistance

from the UNRRA, Yugoslav agricultural and industrial productions gradually

recovered from the catastrophic effects of the Second World War. (see Table

1.1). In agricutural aspect, major crops production increased steadily during

1946 to 1950. Regarding the recovery of domestic industry, Yugoslavs were proud

to claim that their industrial output in 1947 was 120.6 percent of the pre-war

1939 level (Dennison 1977: 21).

Table

1.1: Production of Selected Corps in Yugoslavia, 1946-50* (thousands of metric

tons)

|

|

1946 |

1947 |

1948 |

1949 |

1950 |

|

Wheat |

2,136 |

1,905 |

2,400 |

2,586 |

2,500 |

|

Rye |

241 |

203 |

203 |

229 |

229 |

|

Corn |

2,693 |

5,080 |

4,696 |

4,824 |

5,000 |

|

Barley |

429 |

381 |

404 |

412 |

400 |

|

Oats |

312 |

305 |

327 |

335 |

330 |

|

Total |

5,811 |

7,874 |

8,030 |

8,366 |

8,459 |

|

Pig Iron |

82.8 |

163.0 |

172.0 |

185.0 |

200.0 |

|

Raw Steel |

202.0 |

150.0 |

200-235.0 |

235-250.0 |

250-275.0 |

|

Rolled Product |

148.0 |

145.0 |

175.0 |

178.0 |

180.0 |

|

Lead |

10.7 |

40.0 |

57.0 |

70.0 |

65.0 |

|

Zinc |

4.6 |

5.0 |

8.0 |

10.0 |

20.0 |

|

Aluminum |

2.4 |

3.0 |

2.4 |

2.8 |

2.0 |

|

Crude Oil |

21.3 |

38.6 |

36.3 |

63.0 |

100.0 |

|

Electric Power (billion

KWH) |

1.4 |

1.6 |

2.0 |

2.2 |

2.7 |

*Source: Central

Intelligence Agency. (1977) Economic

Situation in Yugoslavia. CIA Historical Review Program

Release in Full. 22.

In

the meantime, Soviets were trying to increase Yugoslavia’s economic dependence

on Soviet Union and other satellites countries. “For this reason, in the years

immediately after World War II Russia and the other Eastern countries purchased

many of Yugoslavia’s products and supplied their own goods in return”

(Sternberg 1952, 226). Soviet bloc countries’ imports and exports shared a very

large portion in Yugoslavia’s economy, which were exploited as political

instrument to subdue Yugoslavia under Soviet authority. In 1947, Soviet Union

shared 22.2% in total value of Yugoslavs import in 1947 and 16.8% in export. In

the same year, Soviet bloc countries shared 56.1% of the whole Yugoslav imports

and 52.7% of the exports (A.Z. 1956, 38-46). From the beginning of 1949 to June

1949 the economic isolation of Yugoslavia from the Comecon (The Council for

Mutual Economic Assistance led by Soviet Union) led to the dramatic drop in the

total amounts of Yugoslav exports and imports(see Table 2), which forced

Yugoslavia to reorient their economy more closer to Western economy (Ceh 1998,

167).

Table

1.2: Share of the Soviet Bloc Countries in Yugoslav Trade, 1947-1949*

|

|

Imports(per cent) |

Exports(per cent) |

||

|

|

1947 |

1948 |

1947 |

1948 |

|

U.S.S.R. |

22.2 |

10.8 |

16.8 |

15.0 |

|

Czechoslovakia |

17.6 |

17.1 |

18.8 |

15.9 |

|

Hungary |

5.0 |

4.4 |

8.3 |

9.0 |

|

Poland |

3.2 |

7.4 |

3.4 |

7.8 |

|

Bulgaria |

3.2 |

1.7 |

1.8 |

1.0 |

|

Romania |

0.6 |

1.7 |

0.9 |

0.6 |

|

Albania |

0.2 |

- |

- |

- |

|

E. Germany |

4.1 |

2.6 |

2.7 |

1.4 |

|

Total |

56.1 |

45.7 |

52.7 |

50.7 |

|

|

Exports(million

dollars) |

Imports(million

dollars) |

||||||

|

|

1948 |

1949 |

1948 |

1949 |

||||

|

Albania |

12.4 |

- |

6.0 |

- |

||||

|

Bulgaria |

6.8 |

- |

16.6 |

- |

||||

|

Czechoslovakia |

48.6 |

8.6 |

52.2 |

17.7 |

||||

|

Hungary |

26.8 |

3.9 |

13.9 |

6.5 |

||||

|

Poland |

23.7 |

5.0 |

23.1 |

6.5 |

||||

|

Romania |

3.1 |

- |

5.4 |

- |

||||

|

Sovzone Germany |

4.5 |

- |

12.1 |

- |

||||

|

Sovzone Austria |

6.2 |

- |

5.0 |

- |

||||

|

USSR |

45.5 |

9.1 |

337. |

4.7 |

||||

|

Total (from bloc) |

177.6 |

26.6 |

168.0 |

35.4 |

||||

|

Total (global) |

292.2 |

176.7 |

292.5 |

216.5 |

||||

*Source:

A.Z. (1956) The Soviet-Yugoslav

Economic Relations 1945-1955. The

World

Today. Royal Institute of International Affairs. 12(1):

36-38; Central Intelligence Agency. (1977) Economic

Situation in Yugoslavia. CIA Historical Review Program Release in Full. 22.

After

the Soviet Blockade: United States Relaxing Export and Import Control

The UNRRA aid ended in

June 1947 because of mutual distrust—Americans feared Yugoslav would use this

aid to support the popular Greek Communist Revolution, while Yugoslavs feared

economic aid would become a tool for American to demand Yugoslav political

concession in other issues. Without the generous support of UNRRA, Yugoslav

government requested American to release Yugoslavs prewar gold reserves held in

New York. Yugoslavs prewar loyal family transferred gold valued more than $100

million to the Federal Reserve in April 1941 (Jovanov 2009, 54-56). American

rejected the Yugoslavs request and “demanded compensation for the American

assets located in Yugoslavia and nationalized by Yugoslav government. In later

1948 Yugoslavs repeated their demand for the release of the gold held in the

Federal Reserve(Ibid.). Finally in the end of 1948 American decided to unblock

the gold reserve after the settlement with American firms(Ibid.).

The economic

blockade by Comecon, combined with Yugoslav doubled military budget and rising

foreign debt, pushed Yugoslav leaders turn to Americans for help. “If the U.S.

and the West wanted to use Yugoslavia as a wedge to disrupt the communist

movement, they would have to keep Tito’s economy afloat”(Heuser 1989, 81).

“…The West simply had no choice. Yugoslavia was going to be ruled either by

Tito or by a Stalinist puppet. The Kremlin would have its way in Yugoslavia if

the United States failed to come to Tito’s aid.”(Swissler 1993, 86-98).

Yugoslav

Export and Import to United States increased dramatically in 1948. At the

beginning of 1949, Yugoslavia export licenses were approved for a total of

$6,833,000. The United States also approved 10 oil well drilling rigs to be exported

to Yugoslavia. In September 1949, Yugoslavia renewed its export license to

purchase an American mill for steel production. Not only the license was

approval at the end of August 1949, but also Yugoslavs received $3.2 million

for this project (Jovanov 2009, 64-68). In 1947, the value of Yugoslav import

to U.S. was $11.0 million. This figure dramatically rised to $31.0 million in

1948. In 1948, Yugoslav export to U.S. totaled $8.0 million, which increased to

$17.0 million in 1948. (Lampe J. and Russell R. 1990, 30)

The

amounts of American license approval and denial increased significantly after

1948, which signalized the growing relationship between Yugoslavia and United

States. From National Security Council Progress Reportsin May 27 and November 9

(NSC 18/2 Progress Reports) in 1949 we can clearly see Yugoslavs growing

frequent economic contact with United States. During February and April 1949,

licenses approved amounted to $14,569,206. This amount in two months is about

20 percent, or some 2.5 million dollars, higher than the total applications

approved during all of 1948 (National Security Council May 27 1949). The

licenses denied during February and April 1949 is valued $8,122,615, of which about 85 percent, or $6,746,447, was

accounted for by the denial of applications for 10 of the total of 20 oil well

drilling rigs (Ibid.). In Autumn of 1949, the values of export licenses grew

from $876,692 in August to $8722,410 in September (Ibid.).

It is worth mentioning that total valued $80,595 of the

1-A items were approved to be exported in August and $480,549 of the 1-A items

approved in September (Ibid.). The approval of 1-A items to Yugoslavia shows

the Americans effort to secure Tito’s regime against the potential Soviet

invasion. 1-A items were restricted to be exported because “Class 1-A consisted

of munitions, equipments and materials primarily used in the production of

munitions that would contribute to the military potential of the Soviet

bloc”(U.S. Department of State 1948). American officials thought American

willingness to consider to export 1-A items to Yugoslavia “would clearly signal

Tito that the United States wished to contribute to his survival”. In August,

the 1-A item’s licenses approved covered one tinplate order valued at $137,233,

another hot dipped coke tinplate item worth $110,000, and jeep replacement

spare parts of $110,000 value. In the next month, the license for tracklaying

tractors worth $295,236 was approved along with the drilling equipment

(National Security Council Nov.9 1949). Although Americans approval of 1-A

exports to Yugoslavs were in exchange for the Yugoslavs closing border for

Greek communist guerrillas, the growing economic contact presented a “striking

opportunity” for United States to develop sound trade with Yugoslavia”

(Swissler 1993, 75-76).

Sustaining “Tito Effect” in the Soviet Bloc: United

States Extension of Credits and Loans to Yugoslavia

Yugoslavs economy suffered great losses from the

comeinform economic blockade whih started in the beginning of 1949. Learning

from the catastrophic effect of over economic dependence to the Soviet bloc,

Yugoslavs leader became increasingly aware of the need to have more frequent

economic interaction with the West, especially the United States. The Yugoslav

trade deficit had increased to $20 million in the year 1948 and to $50 million

in May 31, 1949. Although American achieved agreement with Yugoslavs about the

royal family’s prewar gold reserve in the Federal Reserve, $20 million of the

total $30 million reserve had already been used for Yugoslav current imports.

In May 1949, Yugoslavs demand for export credits of $25 million to

purchase material resources from the American Export-Import Bank was approved.

In August, another Yugoslavs request for a $20 million loans was approved

(Lampe and Russell eds. 1990, 32). In December, new American ambassador to

Yugoslavia V. Allen met with Tito and Yugoslav foreign minister Kardelj. Both

of them expressed their willingness to further develop Yugoslav economic

relation with United States. Now both sides had consensus, but the problem for

American is, how much Yugoslavs needed? As a staff in Yugoslav embassy

Abramovic described, Yugoslavia needed emergent aid from United States because

of the trade deficit as previous mentioned and the balance of payment crisis

which “if not addressed without delay, would halt all Yugoslav imports” (Ceh

1998, 98-107). For Abramovic, a credit of $25-30 million was in grave need for

Yugoslavs to purchases essential current imports and equipments.

Failure to achieve the goal would result in serious unemployment and harsh

economic situation which would greatly affect the stability of Tito’s regime

(Ibid.). The Yugoslavs ambassador to United States Kosanovic also expressed

that “Yugoslavia pending application before the World Bank for a general loan

of $500 million, of which $200 million would be used for specific projects in

the field of agriculture, mining, and industry” (Ibid.).

Even if

American agree to aid more, how Western economic aid could help Yugoslav

economy? Yugoslavs “Self-Management” socialist economy has its very distinctive

characters that are different from both the Soviet style economy and the

Western style economy. First, different from the Soviet Command Economy,

Yugoslavs self-management economy has no absolute authority that could

determine the economic development. Second, in joint ventures aspect, “Yugoslav

enterprises and foreign enterprises would be defined by special agreements

based on sharing profit and not on property ownership (Sarkovic 1986, 65-68).

Thus the foreign investors could not gain their own property in Yugoslavia.

Also, Yugoslav decentralized bureaucratic economy undermines Americans

willingness to invest because of the political uncertainty and risk. And the

lack of real information about the Yugoslavs economy obstruct those

international financial organization’s evaluation, hence major financial

organizations would not easily approve credits or loans to Yugoslavia. Yugoslav

foreign minister Kardelj claimed that if the West fails to provide economic aid

and Yugoslav economic situation continues to decline, it will create a fertile

soil for pro-Cominform agents in Yugoslavia to overthrow the Tito’s regime

(Swissler 1993, 99-100). He also claimed that Yugoslavs need to obtain a $6

million loan from the International Monetary Fund, $20 to $25 million from the

International Bank and $5 million from the Export-Import Bank immediately (U.S.

Department of State 1950).

United States

and the West actively offered generous economic aid to Yugoslavia to “keep Tito

afloat”. Immediately after the expulsion from Cominform, Yugoslavs received $17

million from United States. In August, Yugoslavia request for additional aid

was approved and it received a $20 million additional loan (Lampe and Russell

eds. 1990, 30). By October 1949, the International Monetary Fund offered a loan

of $3 million to Yugoslavia. In December 1949, West Germany signed a trade

agreement worth of $60 million with Yugoslavia under U.S. auspices. Britain

also signed a five-year $616 million trade agreement with Yugoslavia. United

States used its role in various international and domestic financial

institutions to provide economic aid to Yugoslavia. In 1949, Yugoslavia

received tremendous financial support from International Monetary Fund(IMF),

American Export-Import Bank, and other western countries’ banks. Under the

principle of “keeping Tito afloat”, American Export-Import Bank offered $20

million credits and loans to Yugoslavia in the single year of 1949.(see Table

2.1). On March 1 1950, the American Export-Import Bank granted another $20

million credits for Yugoslavs to purchase goaods and capital equipments.

|

Sources |

Amount |

|

International Monetary

Fund |

900,000

dollars |

|

American Export-Import

Bank |

20,000,000

dollars (interest rate 3.3%) |

|

Britain |

8,000,000

pounds (interest rate 5%) |

|

The Midlands Bank |

2,000,000

pounds (interest rate 5%) |

|

Netherland |

10,000,000

Dutch guilders (interest rate 5.5%) |

*Source: F.

Singleton. 1976. Twentieth-Century

Yugoslavia. Columbia University Press.

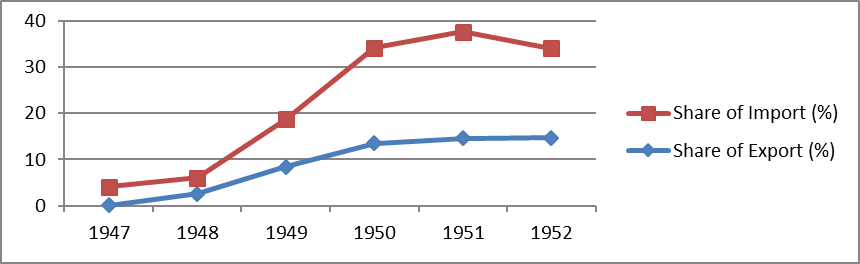

Mutual Trade

between United States and Yugoslavia grew significantly during 1947 and 1952 to

compensate Yugoslav losses from the Cominform blockade. The value of Yugoslav

exports grew from $3.5 million to $36.0 million in 1952, while value of imports

grew from $7.0 million to $146.6 million in the peak year of 1951.

*Source: Savezni Zavod za Statistiku. 1982. Razvoj Jugoslavije. 1947-1981.

Beograd 124;Lampe J. and Russell R. (1990). Yugoslav-American

Economic Relations since the World War II. Durham and London. Duke

University Press. 41.

From Table 2.2

We can clearly see that U.S. shares of Yugoslavs export continue to grow

steadily and reach the peak level—14.7% in 1952. In the meantime U.S. shares of

Yugoslavs import increased dramatically during 1947 and 1949, and it reached

the peak level—19.3% in 1951.

In

1951 Yugoslavia received a loan of $200 million from the International Bank for

Reconstruction and Development (IBRD). Later the approval of “the U.S. Mutual

Security Act of 1951 made the congressional funding possible, and soon

President Truman used his executive authority to support these grants (Ibid.,

40-41). “The International Monetary Fund exchange stabilization loan and the

Export-Import Bank loan aided the process of realignment of Yugoslav trade with

the West, but Yugoslavia also needed massive amounts of assistance from a

number of countries to offset the losses from the Soviet Union and Eastern

European satellites” (Swissler 1993, 183). United States actively mobilized

other financial partners in the West to aid Yugoslavia. From Table 2.3 we can

clearly see many Western countries such as previously mentioned Britain and

France, and those who just recovered from the catastrophic effect of the Second

World War, participated in the Americans program of “keeping Tito afloat”. For

Yugoslav leaders, growing frequent contacts and warming economic relation with

the West, especially with the United States, not only compensate their previous

economic losses from the Cominform blockade, but also decrease the potential

risk of a Soviet military invasion or political subversion. By providing economic

aid to foster the stability of the Tito’s regime, Americans were actually

implementing the wedge tactic toward the Soviet bloc. “the Central Intelligence

Agency(CIA) suggested that his[Tito] survival under Stalin’s pressure could

make it harder for the Kremlin to discipline other similar factions within the

bloc (Lees 1997. 52-53). “American policy toward Yugoslavia rested on a

cold-blooded calculation of self-interest on both sides (Campell 1967, 28).

U.S. economic aid was “small price to pay for what was the one strikingly

successful policy the U.S. was able to conduct in Eastern Europe during the

whole period since the war” (Ibid.). By fostering Tito’s heretical process of

drifting away from Soviet control, Americans could pursue a policy of fostering

division within the Soviet bloc (Jovanov 2009, 101).

|

Source |

Amount (in million dollars) |

|

International Bank for

Reconstruction and Development |

30.7 |

|

International Monetary |

9.0 |

|

American Export-Import

Bank |

55.0 |

|

West Germany |

58.0 |

|

Britain |

47.6 |

|

Switzerland |

16.1 |

|

France |

14.3 |

|

Austria |

10.0 |

|

Egypt |

8.0 |

|

Netherland |

4.2 |

|

Norway |

0.3 |

|

Total |

267.2 |

Food

Aid to “Deflector” from Soviet Bloc: The Yugoslav Drought of 1950 and American

Emergency Relief Assistance

The catastrophic effects

of the severe drought in Yugoslavia posed real threat to the very existence of

Tito’s regime. The total loss caused to Yugoslav agriculture by the drought

amounts about 21 billion dinnars. Productions of major food for citizens’

consumption dramatically decreased: the reduced rates of productions of wheat,

corn, potatos, and fodder are 26%, 35%, 30%, and 20-35% (National Security

Council 1950).

The

Drought of 1951 led to the severe decline in Yugoslavs living standard. In both

rural and urban scale, extreme saving of food needed to be implemented in order

to survive the Drought. In the National Security Progress Report on October 16,

1950, American provided some advices for Yugoslavs to satisfy the country’s

minimum requirements such as slaughtering and exporting certain amount of

livestocks (National Security Council 1950). In order to maintain the minimum

demand, American suggested Yugoslavs slaughter 2.25 million heads of cattles,

4.20 million heads of sheep, and 3 million heads of pigs. American also suggest

Yugoslav could export 50,000 heads of cattles, 100,000 heads of sheep, and

10,000 heads of horses (National Security Council 1950).

The

Drought greatly affected Yugoslavs import in 1951. Yugoslavs had to increase

their budget to import much more agricultural goods in order to survive the

Drought.

|

Item |

Tons |

Dinars 000’s omitted |

Dinars 000’s omitted |

|

Edible Fats |

40,000 |

520,000 |

10,400 |

|

Corn |

100,000 |

350,000 |

7,000 |

|

Wheat |

50,000 |

213,000 |

4,260 |

|

Vegetables and Rice |

|

350,000 |

7,000 |

|

Beans |

30,000 |

244,000 |

4,880 |

|

Sugar |

35,000 |

300,000 |

6,000 |

|

Oats |

100,000 |

250,000 |

5,000 |

|

Barley |

50,000 |

150,000 |

3,000 |

|

Fodder |

50,000 |

125,000 |

2,500 |

|

Seeds |

|

200,000 |

4,000 |

|

Total |

|

2,702,000 |

54,040** |

*This list shows victuals which Yugoslavia has to

import and which ordinarily are not imported articles.

**Real needs for the imported quantities of victuals

are greater on account of the total losses causes by the drought, however, this

list shows the most necessary minimum.; Source: National Security Council.

1950. National Security Council Progress Report on the Implementation of United

States Policy toward the Conflict between the USSR and Yugoslavia (NSC 18/4)

and Economic Relations between the United States and Yugoslavia (NSC 18/2).

October 16.

The formal

request to United States for assistance from Yugoslavia occurred on October 20,

1950 estimated the total need for food assistance at approximately $55 million.

Later, this figure increased to $75 million. By October 3, Yugoslav losses had

amounted to $105 million “that could only be overcome by extraordinary

assistance from abroad” (U.S. Department of State 1950). United States launched

the Stop-Gap Aid Framework, which totaled approximately $33,500,000 for food

purchases and delivery involved the Economic Cooperation Administration, the

Export-Import Bank and Mutual Defense Aid Funds. All three institutions and

programs provided emergent funds for Yugoslavia to purchase food. “The Economic

Cooperation Administration arrangements for the delivery of wheat flour in the

amount of $11,500,000 to Yugoslavia. The Export-Import Bank made available to

Yugoslavia credits of about $6 million for the purchase and transport of food

(lard, beans, dried eggs, and canned meat). The Mutual Defense Assistance

Program under the Mutual Defense Assistance Act provided Yugoslavia with

certain foodstuffs including wheat flour, corn, barley, lard and sugar (Whilte

House Central Files, 1950).

American plan

to provide food aid to Yugoslavia could be divided into two stages. The first

stage, U.S. officials could provide the first emergent food aid to Yugoslavia

without Congressional approval. The first aid valued $30.8 million, provided

Export-Import Bank, Mutual Defense Assistance fund, and Economic Cooperation

Administration fund. The second aid needed Congressional approval. It included

125,000 tons of corn, 125,000 tons of feed grain, 50,000 tons of vegetables and

15,000 tons of seed (U.S. Department of State 1950, 1489-1499).

In

December 1950, the Emergency Relief Act was passed by Congress and Yugoslavia

received $50 million in relief, with another $38 million under the Marshall

Plan (Lampe J. and Russell R. 1990, 37). The Congress appoved the second stage

of food aid to Yugoslavia containing 125,000 tons of corn, 125,000 tonso feed

grain, 50,000 tons of vegetable and/or rice, and 15,000 tons of seed (U.S.

Department of State 1950, 1489-1499). In the whole year of 1950, Yugoslavia

received $6.1 million from American Export-Import Bank to purchase procured

beans, eggs and canned eggs, $12.5 million from Mutual Defense Program to

purchase 9,000 tons of lard, 32,000 tons of flour, 25,000 tons of sugar, and

$12.2 million to purchase 110,000 tons of flours.

Conclusion

The

goal of United States generous economic and food aids to Yugoslavia is to “keep

Tito afloat,” which is equal to maintain existence of Tito’s regime, against

the Soviet bloc. After the end of the Second World War, the fundamental

strategic orientations of Soviet Union and Yugoslavia began to diverge. The

Soviets expulsion of Yugoslavs out of Cominform signalized the total split

between Tito and Stalin.

For American,

although Yugoslavia is a communist country, its expulsion by Soviets

demonstrate that Soviet bloc countries are not united together against the

West. Using economic aid to further widen the gaps among bloc countries became

a feasible choice for Americans.

Firstly,

immediately after the Second World War, U.S. led Western world provided

tremendous material support to Yugoslavia through the form of UNRRA. The aid

from UNRRA helped Yugoslavs to rebuild and rehabilitate agriculture, industry,

and economy. In June 1947, UNRRA aid to Yugoslavia came to an end due to mutual

suspicions toward each others’ intentions.

After the

Soviet-Yugoslav split, Soviet Union launched a total economic blockade together

with other Cominform countries. Due to Yugoslav highly dependent economic

relationship with Soviet bloc, the severe losses result from the Cominform

blockade posed a real threat to the Tito’s regime. By keeping Tito afloat under

the pressure from Soviet bloc, American actually was encouraging other bloc

countries to rise up against Soviet hegemony. Americans continued to expand

their economic relation with Yugoslavia in order to offset Yugoslavs losses

from the Cominform blockade. United States actively mobilized domestic and

international financial institutions such as Export-Import Bank, Federal

Reserve, Economic Cooperation Administration, World Bank, and International

Monetary Fund to extend credits and loans to Yugoslavia. U.S. share of export

and import in Yugoslav economy quickly increased as a result of more and more

frequent economic interactions.

In 1950,

severe Drought hit Yugoslavia which causes dramatic declines in Yugoslav

agricultural production and foreign trade. American quickly responded by

providing Stop-Gap aid. The Congress passed the Emergency Relief Act of 1951

which allowed United States to provide emergent food assistance to Yugoslavia

using funds from previous mutual framework such as Mutual Defense Act, Mutual

Security Act, and previously mentioned financial institutions.

“Yugoslavia’s

continued fight against Soviet threat was now acknowledged to be in the

national interests of the United States.” By providing economic aids to

Yugoslavia, their struggle to overcome the effects of the Cominform economic

blockade had been successfully concluded by an orientation of Yugoslavia’s

international economic relations westward. Finally U.S. Congress in 1951

announced Yugoslavia no longer stood alone in its resistance to Cominform aggressive

pressure (U.S. Congress 1951, 12).

Bibliography

A.Z.

(1956) The Soviet-Yugoslav Economic

Relations 1945-1955. The World Today.

Royal Institute of International Affairs. 12(1): 36-38.

Campell

J. (1967) Tito’s Separate Road: America

and Yugoslavia in World Politics. 28. New York. Harper & Raw

Publishers.

Ceh

N. (1998) United States-Yugoslav

Relations During the Early Cold War. 1945-1957. 167. 98-107. University of

Illinois at Chicago PhD Thesis.

Central

Intelligence Agency. (1977) Economic

Situation in Yugoslavia. CIA Historical Review Program Release in Full.

17-20. 24.

>Jovanov

S. (2009) Yugoslav-American Relationships

during the Truman Presidency: Truman’s Eggs and Tito’s Separate Road. 8-30.

54-56. 64-68. 70-75. 101. University of Alabama in Huntsville PhD Thesis.

Lampe

J. and Russell R. (eds.) (1990) Yugoslav-American

Economic Relations Since World War II. 21. 32. 30. 40-41. 37. Durham. Duke

University Press.

Lees

L. (1997) Keeping Tito Afloat: the United

States, Yugoslavia, and the Cold War. 52-53. University Park. the

Pennsylvania State University Press.

National Security Council. (1949) National Security

Council Progress Report by Acting Secretary of States on the Implementation of

Economic Relations Between the United States and Yugoslavia (NSC 18/2), May 27.

National Security Council. (1949) National Security

Council Progress Report on the Implementation of Economic Relations Between the

United States and Yugoslavia (NSC 18/2). November 9.

National

Security Council. (1950) National Security Council Progress Report on the

Implementation of United States Policy toward the Conflict between the USSR and

Yugoslavia (NSC 18/4) and Economic Relations between the United States and

Yugoslavia (NSC 18/2). October 16.

Sarkovic

T. (1986) Direct Foreign Investment in

Yugoslavia: A Microeconomic Model, 65-68. New York.

Savezni

Zavod za Statistiku. (1982). Razvoj

Jugoslavije. 1947-1981. Beograd. 124.

Singleton

F. (1976) Twentieth-Century Yugoslavia.

Columbia University Press.

Sternberg

F. (1952) “Tito’s Unique Yugoslavia.” The

Nation. CLXXIV. March 8. 226

Swissler

J. (1993) The Transformations of American

Cold War Policy toward Yugoslavia. 1948-1951. 86-98. 75-76. 99-100. 183.

309. University of Hawaii PhD Thesis.

U.S.

Congress. (1951) U.S. Congressional Record. 81st Congress, 2nd

Session, 96:12.

U.S.

Department of Stale. (1951) Memorandum of Conversation, Signed by Acheson,

October 20, 1950. Papers of Dean Aceson. Box 64. Harry S. Truman Presidential

Library. Independence, Missouri, 1; U.S. Congress, House of Representatives,

Committee on Foreign Affairs, Yugoslav Emergency Relief Assistance: Letter from

the Secretary o f State, 82nd. Congress, 1st Session, House Document No. 112,

Serial No. 822275. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1951)

22-23.

U.S. Department of States. (1948) Foreign Relations of the United States. 4: 546-568.

U.S. Department of States. (1950) Foreign Relations of the United States. 4: 1489-1499.

White

House Central Files. (1950) Memorandum of Press Release for President Truman on

November 29 1950. Box 26, 2. Harry S. Truman Presidential Library,

Independence. Missouri.

*Zeng Qingming - Institute of International Relations, Faculty of Political Science

and International Studies, University of Warsaw, Krakowskie Przedmiescie 26/28,

00-927 Warszawa, Poland e-mail: 1821339784@qq.com

© 2010, IJORS - INTERNATIONAL JOURNAL OF RUSSIAN STUDIES